Wednesday's Ruck & Maul

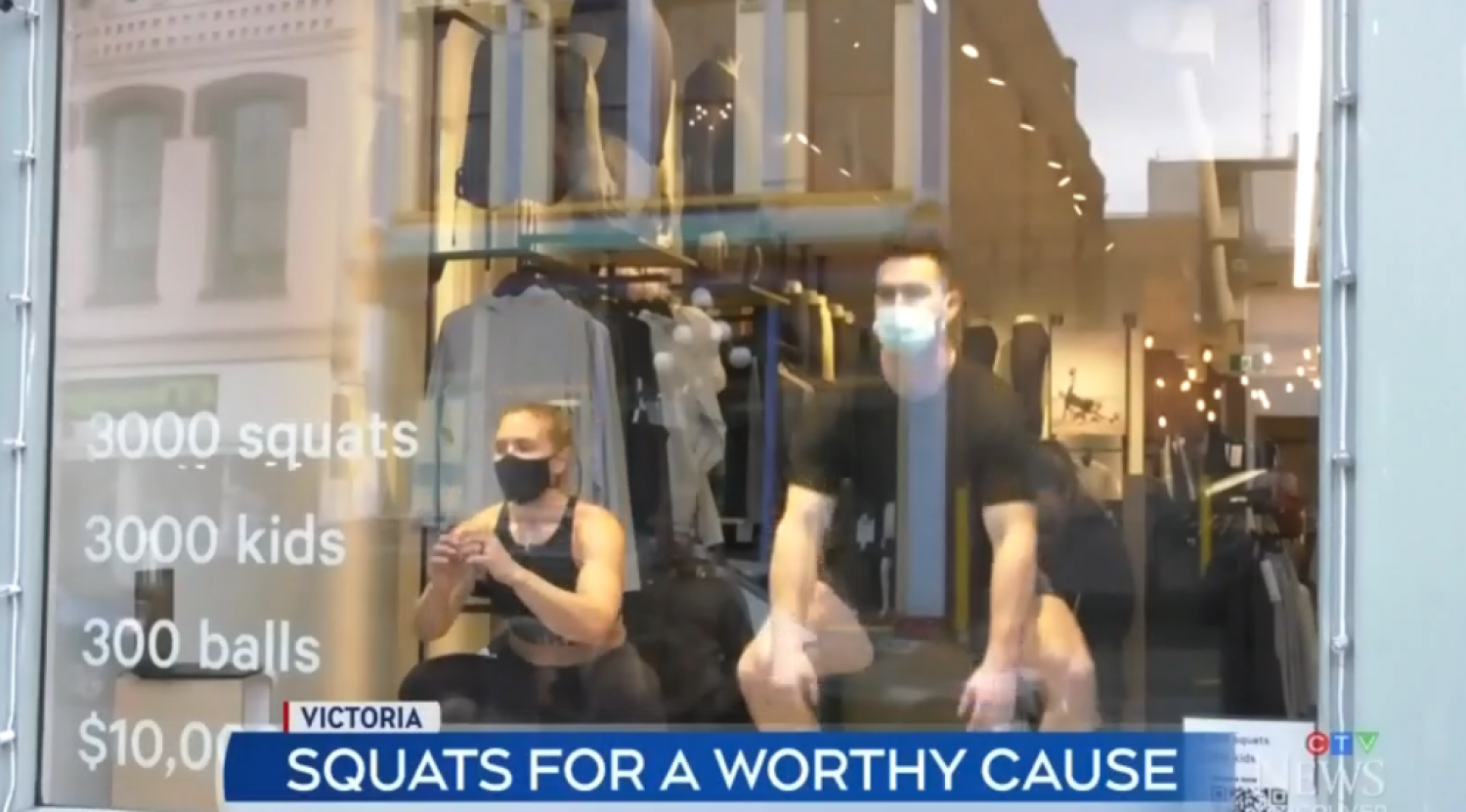

In lieu of CW Minis rugby last weekend and in conjunction with CFAX Santa’s Anonymous, one of CW’s Minis coaches, Baylea Wilkins got on with her task of completing 3,000 squats!! Baylea’s goal was to help 3,000 needy Victorian kids during the coming year. Sports equipment and money were generously forthcoming and as you can see from this video, she was enthusiastically supported. Should you wish to contribute, you are not too late and you can do so by clicking HERE

(Photo, video credit CTV News.) ‘onya, Baylea.

Back In the Day

One of the Faithful recently dug out an excerpt from his musings about his schoolboy days and asked if the site could use it as a “filler”. Use it, we could. The Ruggernut brings you the musings in their entirety for there are so few around that might have experienced such a rugby upbringing, let alone remember it!! For ‘today’s’ young men and women this was what it was like – Back in the Day! Enjoy.

Fonthill Preparatory School 1st XV Rugby 1954 (Author Seated at Left)

I was eight years old in 1949 when I first went to boarding school in the south of England, and it was there that I was formally introduced to team sports: Cricket, Association Football (now known as ‘Soccer’ from the abbreviation, but then as ‘Footer’) and of course Rugby Football, or Rugger. Footer was played in the autumn on a nice level field, still hard and firm after the summer. Rugger however was played in the wet spring on The Paddock: rough tussock grass six inches high and mud churned up by our heavy boots with leather studs. Our coach was Mr. Woodroffe, a former bomber pilot, who brought the same approach to the game: put your head down and go for it, blasting through the flak and enemy fighters. Fifteen-a-side of course right from the beginning, and a badly inflated misshapen laced-up leather ball which weighed a ton when wet, which was nearly all the time. We learned the basics: scrums, lineouts (ball thrown in by the winger and no lifting), running, passing and tackling: hit your opponent between knee and thigh and slide your arms down to bring him down. Some tactics have gone by the board: the cry of ‘Wheel and Take’ would cause puzzlement today, but the ‘Up and Under’ has come back into fashion, even if renamed the Box Kick. After five years of this I became a reasonably competent forward, and we certainly had plenty of practice and matches against rival schools.

Then came a complete change as my family moved to what was then Southern Rhodesia in 1955, and I arrived at the beginning of the rugby term, a lanky fourteen-year-old promptly nicknamed ‘Suntan’: after a gloomy English winter I certainly looked very different from the tanned and sun-bleached Rhodesians. The Under-15A coach was our chemistry teacher, Doc Harris, a tall lean wiry man who coached rugby with a single-minded determination to accept nothing less than the very best from everyone. He would arrive for practice in his enormous rusty Hudson and park this tank-like vehicle by the field. The rugby field itself was a far cry from the muddy paddock where I had learned to play the game: this was an acre of black vlei soil, baked rock-hard by the sun, and was never watered, so the grass was virtually non-existent, and our knees and elbows were always covered with scabs and scars. These conditions made for a different type of game too: fast and open with the emphasis on the backs in place of trench warfare among the forwards. I played lock, mainly on account of my height, but Doc took exception to my scrummaging technique: “Glegg, get lower, man, you look like a bleddy camel!” I packed down as low as I could, but not low enough for Doc. He sent me to fetch a stick from the hedge beside the field, and with its encouragement I quickly learned how to pack down and shove with my hips lower than my shoulders. “That’s much better, man, well done - now we have to work on your line-out jumping.” I was never more than a second team player, but it was Doc who gave me a life-long enthusiasm for the game.

Inter-school rugby was enormously important, and everyone dreamed of the day when the upstart Churchill might beat Prince Edward, the perennial champions. Every boy in the school played rugby – practices twice a week, and a match on Saturday – and on at least one occasion Churchill put 36 teams on the field in a single day. Male teachers were expected to coach rugby as a matter of course, even if they started at the lowly level of the Under 13 C and D squads, which one year had a particularly impressive record: U13C -Played 13; Won 13; Points for 404; Points against 10. U13D - Played 13; Won 13; Points for 310; Points against 24. Results were read out on Monday morning at assembly, and the minor junior teams were given just as much recognition and credit as the high-profile senior teams. Cricket and athletics were also important, but none came close to rugby in the matter of prestige.

Every Saturday when there was a home rugby match the whole school (including nearly all the staff, complete with wives or husbands) would gather on the stands of the Nigel Philip field to watch the 1st. XV; if they were playing against a local rival school such as Prince Edward, there would be well over 2,000 partisan spectators, all dressed in their colourful blazers, and each team had its own war cry. Some, like Prince Edward’s, were quite mild. We felt that our war cry, although meaningless, sounded threateniing and we made an impressive amount of noise!

You don’t have to be good at something to enjoy it. My final school report was quite flattering about my academic ability, but refreshingly frank about my athletic prowess: “As Captain of the Second XV Rugby he has been a success. He has also played cricket.”

(With thanks to Alastair Glegg.)